The Science of Studying: How You Sabotage Learning

Introduction

Studying is not the same as learning.

Studying is about what—the information you encounter and introduce to your mind.

Learning, on the other hand, is about how—the process of synthesizing and making that information usable in the long term.

Many students fall into a false sense of security by confusing the two. And honestly, it’s hard to blame us. From an early age, we’re told to “just study,” but rarely are we taught how to study effectively.

It’s ironic that education is so highly valued in society, yet the very act of learning—how to absorb, retain, and apply knowledge—is often overlooked.

This gap becomes especially glaring in university, where the stakes are high, and we’re expected to excel without being equipped with the right tools. So, let’s start with a working definition:

Studying is what we do to encounter and introduce information. Learning is how we synthesize and make that information usable in the long term.

Imagine putting a hundred students in a room, giving them the same topic, materials, and prior knowledge. Despite these equal conditions, not all of them will achieve the same results.

This discrepancy isn’t due to genetics or a lack of effort—it’s often a mismatch between the difficulty of the topic and the methods used to study it.

Your Methods Are Wasting Your Time

The methods you use to study play a huge role in how effectively you learn. Many students swear by rewriting notes, highlighting textbooks, and using premade flashcards.

But here’s the truth: these methods are often a waste of time.

Productivity isn’t about the number of hours you put in—it’s about how much you get out of those hours.

Ask yourself: how many hours have you spent rewriting notes or highlighting passages? Did those hours translate into better grades?

The reality is, you can spend dozens of hours creating beautifully color-coded notes and still struggle on exams.

For many students, studying becomes a dreaded chore rather than an engaging process. And here’s the thing: learning is supposed to be fun.

Conventional study methods—like rewriting notes, highlighting, and rereading—are not only boring but also ineffective.

Why? Because they rely solely on remembering. While remembering is the foundation of learning, it’s not enough for higher education.

You might confuse remembering with learning when you highlight a sentence or jot it down in your notebook, but that’s not true understanding.

Let me illustrate this with a question: What is the powerhouse of the cell?

You probably answered “mitochondria” without hesitation. But if I asked you why it’s called the powerhouse or how it relates to adenosine triphosphate, could you answer just as quickly? (Unless you’re a STEM major, probably not.)

It’s possible to pass your classes by relying on highlighting and note-taking.

But what if I told you there’s a way to learn more in a quarter of the time? Would you still stick to your old methods?

The Dangers of the Wrong Methods

When you’re faced with a large volume of material and your primary study methods are rewriting notes and highlighting, you’re setting yourself up for overwhelm.

Many students wear sleep deprivation and skipped meals as badges of honor, but these habits don’t contribute to learning—they detract from it.

I once knew someone who proudly bragged about not sleeping or eating because they were “studying” (i.e., rewriting notes).

Sure, their notes looked pretty, but at what cost? Sacrificing sleep, skipping meals, and neglecting joy don’t make you a better learner—they make you resent the process.

In university, your syllabus will cover a wide range of topics with varying levels of difficulty and importance.

It’s impractical to approach every topic with the same mindset: “Writing it down helps me remember.” Especially when some topics might only make up 2% of the exam, while others account for 10%.

Yet, students often spend the same amount of time on both.

To keep up, students sacrifice sleep, skip meals, and ignore their social lives—all while clinging to ineffective methods.

The result? Not only do they risk their grades, but they also jeopardize their health, relationships, and mental well-being.

If these were the side effects of an experimental drug, no one would take it. Yet, for many students, this is the only way they know how to study.

The Science of Learning

Working Memory vs Long-term Memory

The human brain is a marvel.

While it makes up only 2% of your body weight, it consumes 20% of your daily calories. Its storage capacity is estimated at one quadrillion bytes—that’s a one followed by fifteen zeros.

In other words, your brain can store more information than every computer you’ve ever owned combined.

The real challenge isn’t storage—it’s getting information in and out of your brain effectively. This is where two types of memory come into play: working memory and long-term memory.

Think of your long-term memory as a well-organized library. Once information is stored there, it’s relatively easy to retrieve with the right cues.

Your working memory, on the other hand, is like a sticky note—temporary and easily overwritten by the next piece of information.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

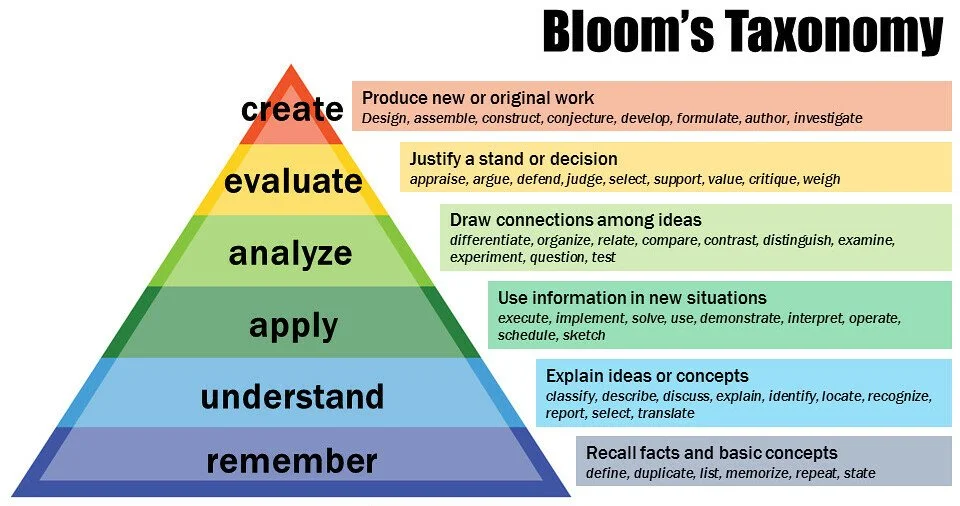

Traditional study methods—rewriting notes, highlighting, and rereading—fall under what’s known as Lower Order Thinking Skills (LOTS).

These methods give you a false sense of security because they rely on surface-level engagement with the material. Under Bloom’s Taxonomy, LOTS include remembering, understanding, and applying.

While these skills are important, they’re not enough for true mastery.

Instead, focus on Higher Order Thinking Skills (HOTS), which include analyzing, evaluating, and creating. These skills force your brain to engage deeply with the material, leading to better understanding and retention.

Rote memorization—like remembering that mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell—doesn’t mean you truly understand the concept. HOTS, on the other hand, make learning more engaging and efficient.

Personally, I relied on HOTS throughout my final year in BS Accountancy and still had time to maintain a gym schedule.

I doubt I would have achieved the same results if I’d stuck to LOTS methods like rewriting notes.

An efficient learning method

Think of your brain as a muscle. To grow stronger, a muscle needs to be progressively challenged. Your brain works the same way.

If learning feels easy, you’re probably not doing it right. True learning requires effort and challenge.

Many students assume that if something feels difficult, it’s not working. But that’s exactly when your brain is building stronger connections.

If you’re not challenging your brain, it won’t adapt—and it will forget.

So, what’s a better alternative to highlighting and rewriting notes? Retrieval practice.

Retrieval practice is the act of testing yourself on the material without relying on your notes or textbooks.

It’s an active form of learning that forces your brain to recall information, strengthening your long-term memory in the process.

This method isn’t a magic bullet—you still need to put in the work. But compared to passive methods like highlighting, retrieval practice is far more effective and engaging.

Instead of hoping you’ll remember a sentence highlighted in bright pink, you’re actively reinforcing your understanding.

Conclusion

Your study time is valuable, but the methods you use determine how much value you extract from it. Rewriting notes and highlighting might feel productive, but they often lead to wasted time and frustration.

Instead, focus on methods that challenge your brain and promote deeper understanding, like retrieval practice and Higher Order Thinking Skills.

Learning doesn’t have to be a chore. By adopting more effective methods, you can study smarter, not harder—and maybe even enjoy the process along the way.